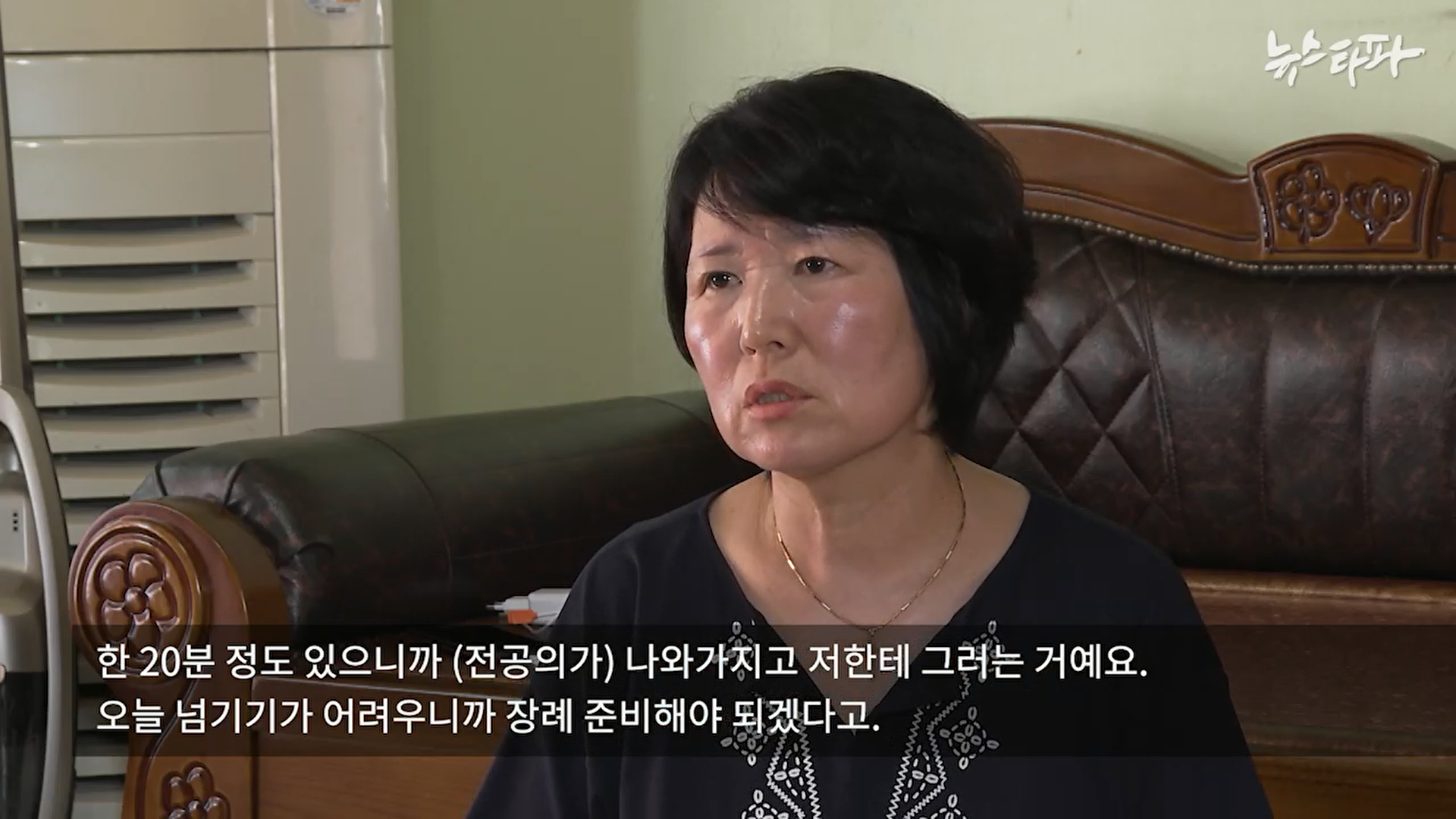

“It was lunchtime then, so there was no one else. I was shaking, jumping and shouting ‘Oh my God, What do I do?’ I screamed to the nurse to make calls and ask for help, and then they made announcements. But the clock was still ticking.”Go Jeong-soon, Jang Gyeong-bok’s wife

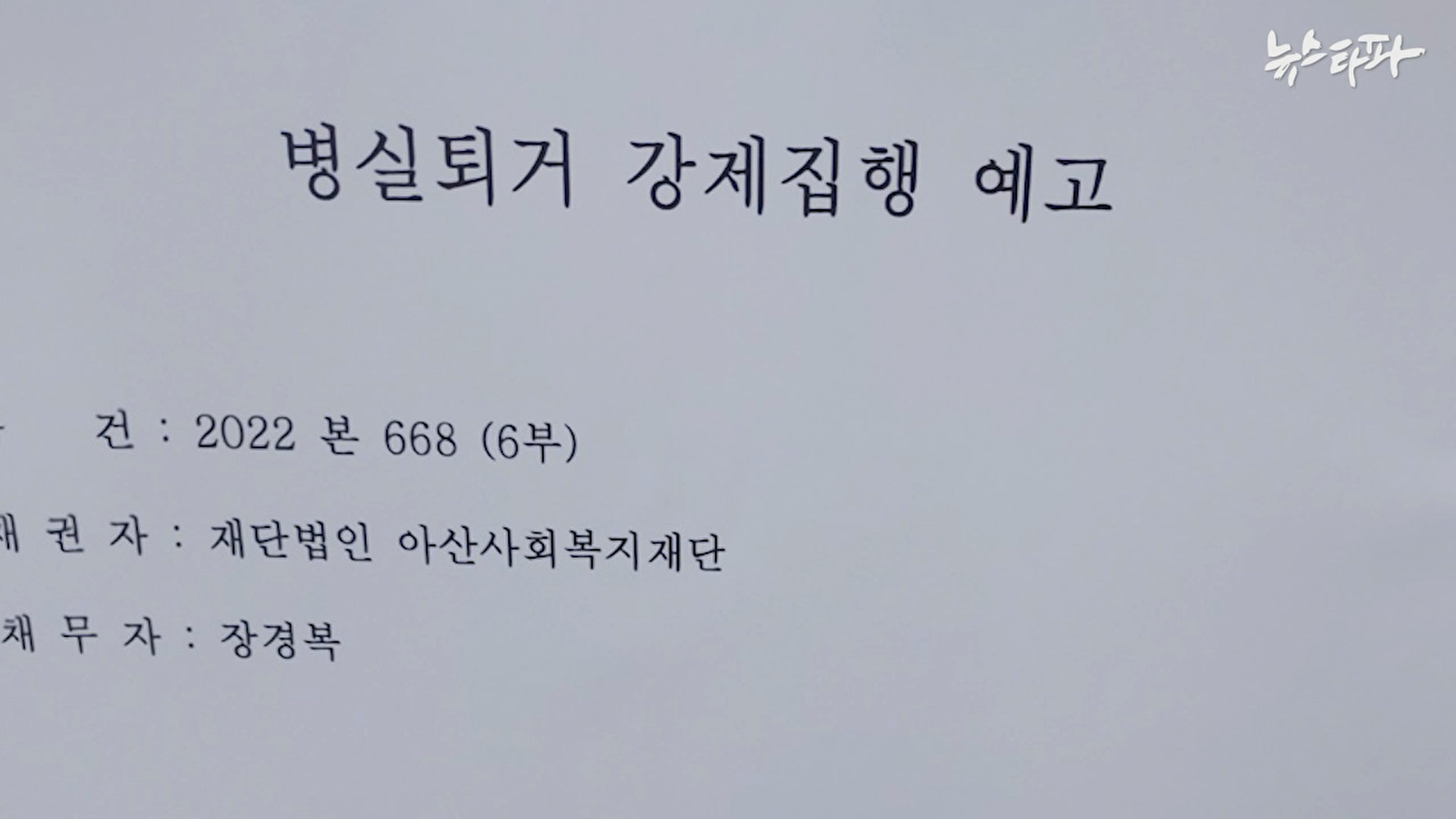

“The hospital staff said, ‘The patient can remain stable if he gets there. He can receive rehabilitation treatment there as well. If he stays here at the intensive care unit, he can’t get that treatment. So he should move.’ You know, we really don’t have much idea about all this. I thought we had to move because he would be able to receive rehabilitation treatment and be treated well there.”Go Jeong-soon, Jang’s wife

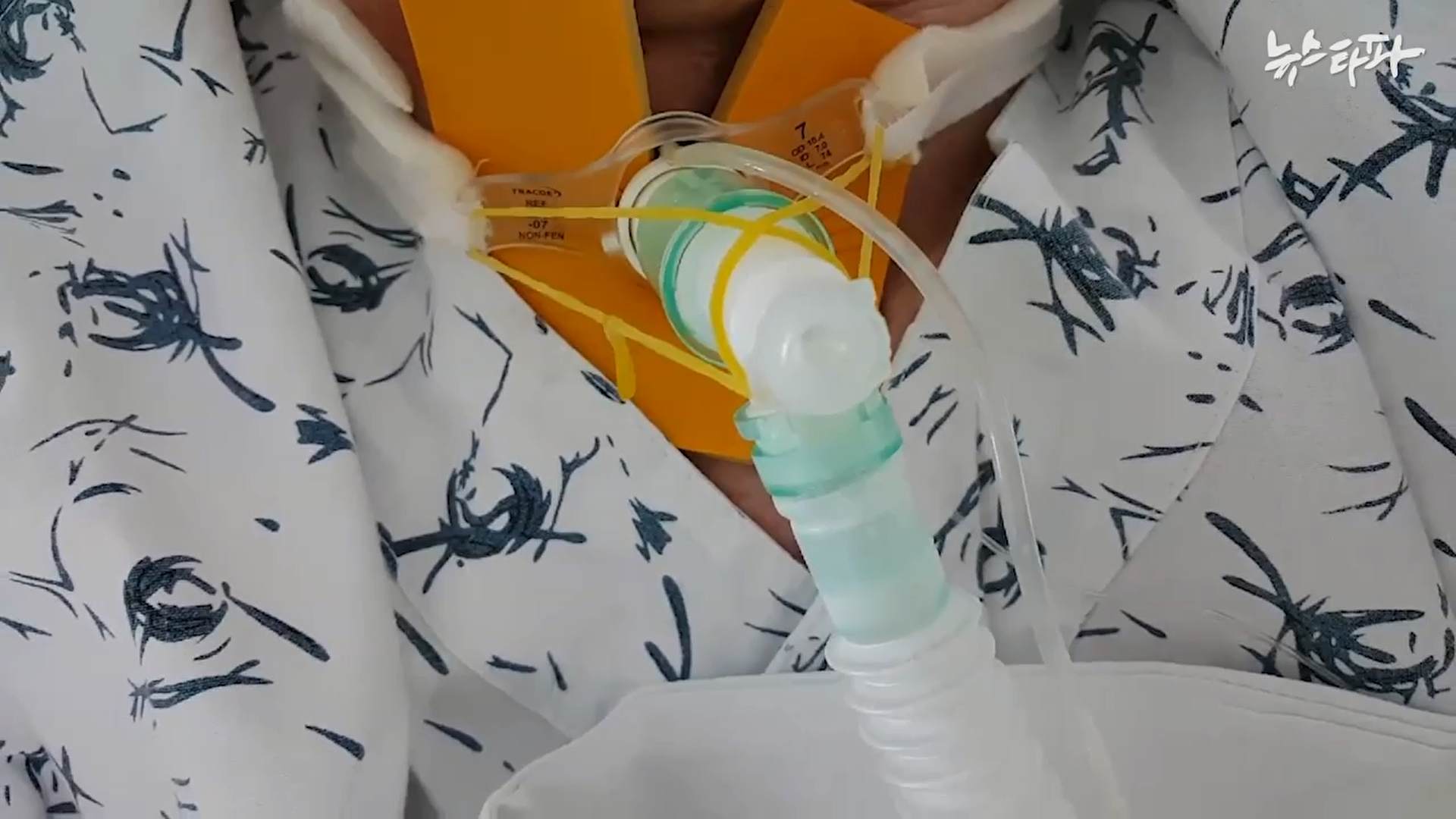

“At the time when the intubated tube was removed on November 28, 2015, the patient was a 51-year-old male, 180cm tall, and weighed 100 kilograms with a body mass index (BMI) of 30.86. He had high blood pressure of 140/97mmHg. Based on records from the first outpatient visit, he had a habit of smoking more than one pack of cigarettes a day for the past 30 years and drank more than two bottles of soju a week.”Asan Hospital’s litigation attorney

“Even though the medical staff performed cricothyroidotomy as an emergency procedure to secure the patient’s airway, the patient was in a physical condition in which it was difficult to find his cricothyroid membrane. He was, because he was highly obese with a body mass index (BMI) of 30.86 and had smoked for more than 30 years. For these reasons and others, the possibility of success was not clear.”Asan Hospital’s attorney

“This study suggests that there was no relationship between body mass index (BMI) and the time taken to perform the procedure, and this implies that patients with airways of complicated shape can receive the procedure in a time similar to that of a person with that of a normal shape.”Yang Hat-bit et al., 2015

“The cause of airway obstruction, in this case, is airway edema (airway swelling) or airway spasm (which also results in airway obstruction). It appeared acutely and could not have been predicted…”Asan Hospital’s legal attorney / Translation of the original text

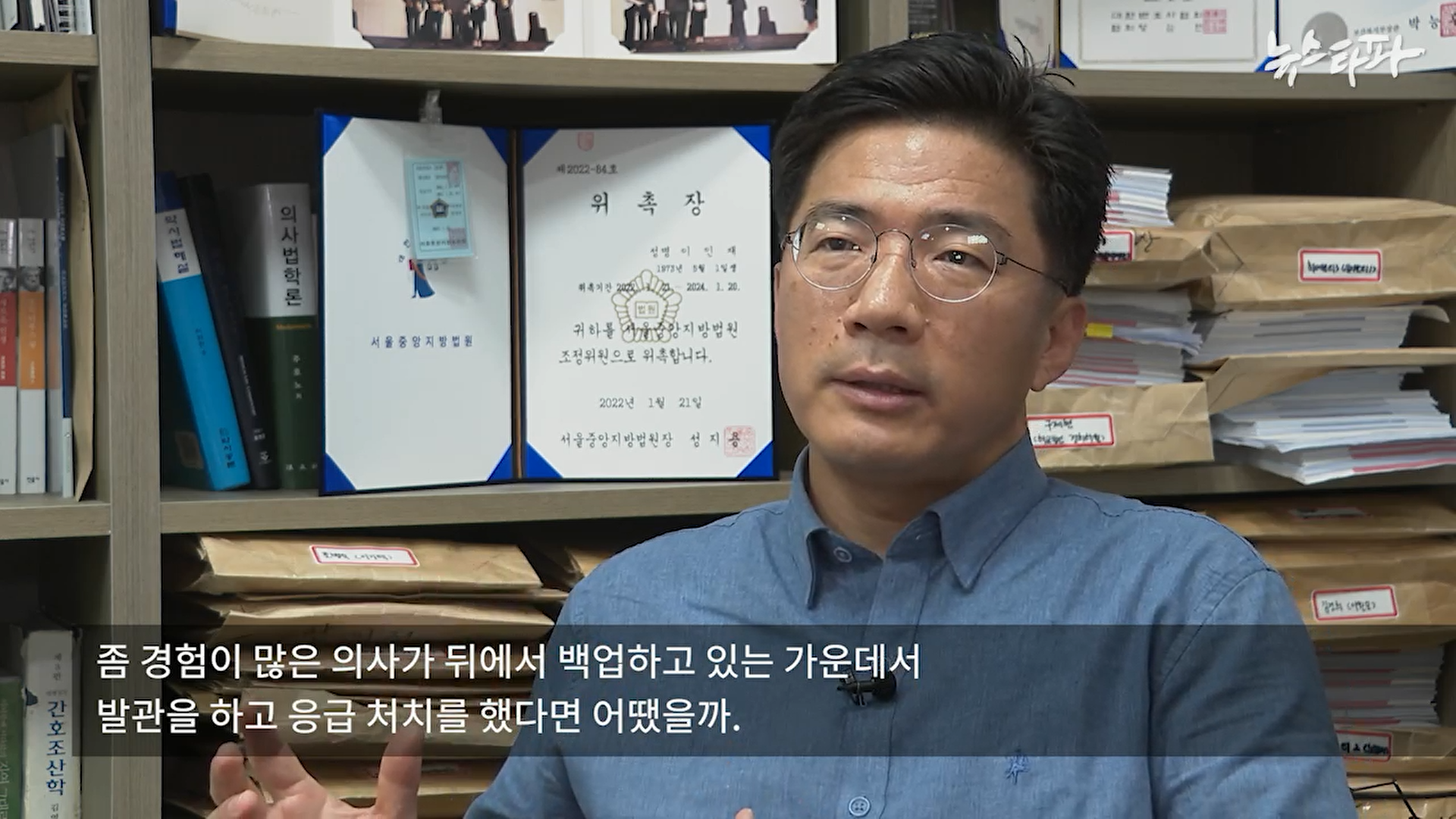

“Conversely, the situation can be interpreted that the patient who was likely to die due to sudden airway obstruction survived with brain damage through appropriate emergency measures by the defendant hospital’s medical staff, and the prognosis improved.”First trial court ruling

“The resident must have learned a lot. ‘The bronchial tube is not to be carelessly removed after neck surgery, and it can lead to an emergency, and shortness of breath in which case immediate emergency treatment should be conducted.’ Other medical staff at Asan Hospital had real-life training on how a dangerous accident like this may occur at the high cost of victimizing the patient. After all, the medical team would act more carefully through this patient’s sacrifice, but it is too harsh for the patient to endure this.”Park Ho-Kyun, Jang’s attorney

| Reporting | Hong Woo-ram, Kang Hyeon-suk |

| Video Reporting | Kim Ki-cheol, Jeong Hyeong-min, Shin Young-chul, Lee Sang-chan |

| Video Editing | Park Seo-young |

| CG | Jung Dong-woo |

| Design | Lee Do-hyeon |

| Web Publishing | Heo Hyeon-jae |

뉴스타파는 권력과 자본의 간섭을 받지 않고 진실만을 보도하기 위해, 광고나 협찬 없이 오직 후원회원들의 회비로만 제작됩니다. 월 1만원 후원으로 더 나은 세상을 만들어주세요.